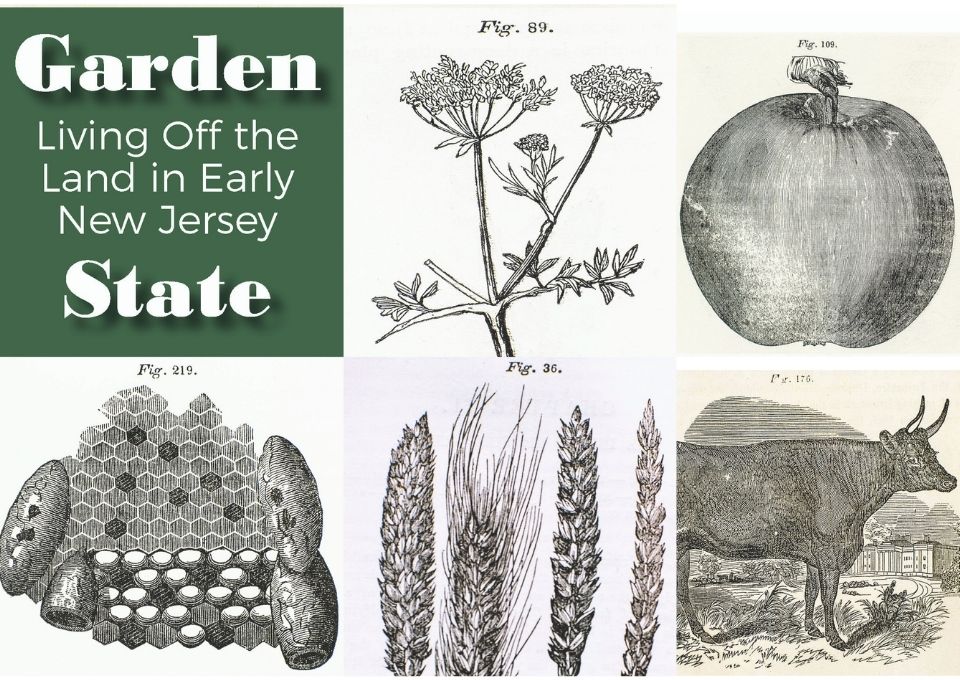

The Garden State

Living Off the Land in Early New Jersey

Garden State: Living Off the Land in Early New Jersey ran from January 17 to September 2, 2017, and explored the technology and tools, from bee smokers to cradle scythes, that farmers in 18th and 19th century New Jersey utilized in order to survive. The exhibit also highlighted the new generation of Garden State farmers who are working to make the distance from farm to table a little bit shorter for today’s families.

How far is the distance from farm to table? Most families in early New Jersey could measure it in inches. These farming families did not make their living “by bread alone.” They relied not only on wheat and corn, but also on bees, cows, apples, and vegetables to support themselves and their communities.

Guests got a peek at the shift in what has been grown on farms over the years. The most intriguing piece of the of the exhibit was discovering that New Jersey was renowned for its cider and even had its own variety of apple.

Objects on Display

The Rose City

industry in Madison began with the professional gardeners who worked on the estates built by wealthy industrialists here in Madison in the nineteenth century. Many of these gardeners eventually established their own greenhouses and grew roses for markets in New York and beyond. One such company was the Joseph F. Ruzicka company, whose roses adorned the United Nations building in New York on its grand opening.

Strong as an Ox

Welcome to Madison, the Rose City! The rose This yoke fit the giant necks of two oxen, the “workhorses” of early America. Farmers in Morris County owned over 1,000 heads of cattle in 1776, and they used their labor as a form of currency. Although farmers owned both cattle and horses, cattle have several advantages over horses:

- Stronger: a team of oxen can haul heavier loads than a team of horses.

- Healthier: oxen are less prone to laminitis, a disease of the feet.

- Cheaper: working horses need grain mixed with hay, but oxen can survive on hay alone.

Rebellious Sheep Shearing

Sheep shearing became a patriotic act during the American Revolutionary War as patriots defied the British Wool Act of 1699. The Act forbade farmers from exporting wool across colony lines, one of many restrictive trade laws that inspired the Revolution.

Farm Equipment

The grain cradle, or cradle scythe, improved upon earlier forms of scythes by adding wooden fingers that kept grain bundles organized in the field as they were cut. This was an early form of a labor-saving agricultural machine.

Common Pests

The Wheat Weevil preys on stores wheat crops. Wheat-growing state closely monitor weevil outbreaks and strictly regulate import and export of grains from infested areas.

The Hessian Fly’s name comes from a theory that the pest first came to America in straw used by the Hessian mercenaries during the American Revolutionary War. Wheat farmers today plant their wheat after the flies are active, or plant fly-resistant strains of wheat.

“Odgen Crane threshed the wheat. Had 20 bushels for 4 acres. The weevil and Hessian Fly destroyed it.” ~ Oscar Lindsley, Green Village, NJ (July 21, 1852)

Apple Preparation

This apple parer, patented by Amos Mosher in New York in 1829, made preparing winter apple faster and easier. It used a type of pulley system to rotate the knife.

Apple Cider

New Jersey, and especially Morris County, is renowned for its cider. The Harrison Apple, a famous variety of New Jersey apple known as the ” champagne of ciders” in colonial times, almost disappeared in the nineteenth century. Thanks to the efforts of scientists and local farms like New Ark Farms in Newark, this famous apple is on its way back.

Thank you to those who made this exhibit possible!

- The Farm at Natirar

- New Ark Farms

- Catherine Coultas

- Kathy Goodbread, Trina Mallik, and students of Kings Road School

- Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries

- Merynda Fuelhart, OozeHealth

- Bobolink Farms (Jonathan and Nina), Matt Stiles

- Provident Bank

- New Jersey Farm Bureau

- Online Exhibit Design: Esther Tobe

- Special Thanks to Exhibition Interns: Abigail Knight, Esther Tobe, James Savakis