The Good Earth

Pottery and Terra Cotta Industries in New Jersey

Good Earth: Pottery and Terra Cotta Industries in New Jersey ran from July 19 to December 31, 2016, and followed the world-famous New Jersey clay industry from the earthenware jugs of the colonial kitchen to the terra cotta masterpieces that shaped American skylines in the late 19th century.

People have appreciated the durability of pottery for thousands of years. In New Jersey, Native Americans began making pottery for storage and cooking before 200 B.C.E. The earliest pottery shops in New Jersey date to the late 1600s. Most of these early potters were farmers with small backyards kilns making pottery for their neighbors from clay they harvested and prepared by hand. Even as the craft of pottery evolved into grander and more decorative forms, the basic technologies and skills of the trade remained the same.

During the late 19th century, artisans and entrepreneurs competed to harvest the rich clay resources of New Jersey’s rivers. More than 40 terra cotta companies called New Jersey home during the state’s six-decade reign as the terra cotta capital of the world. These designs live on in many buildings, including the iconic Woolworth and Flat Iron Buildings in New York.

This exhibit took guests through the history of New Jersey clay and contains a sampling of some fascinating and beautiful local terra cotta objects and artifacts, as well as archival materials and tools of the terra cotta trade. Featured throughout this exhibit were tools and original pottery from the museum’s collection as well as photographs, drawings and examples of ornamental terra cotta pieces. Of special significance in this exhibit are two c. 1899 terra cotta finials from METC’s building, removed for renovation and on display for this one-time-only appearance. Their fleur-de-lis design exemplifies the artistic flair of the late 19th-century terra cotta ornaments. Also on display were examples of modern pottery by two New Jersey potters, Mimi Stadler and Jane Biron, showing how New Jersey clay is still being used today in functional and decorative forms.

Objects on Display

New Jersey Clay Leads the Way (1600-1870)

Earthenware Platter, c. 1800s

Collection of Museum of Early Trades & Craft

The yellow loops and lines contrast against the red background of this earthenware platter, which shows a technique popular with German potters in early America. Potters created the yellow designs with slip, a liquid concoction of clay and water. The free-wheeling design on this platter was likely made by hand with a brush, but similar designs were made with a slip cup, a clay cup with quills jutting from its base that allowed the slip to pour out in colorful parallel lines.

Stoneware Crock, Connolly & Palmer Pottery, c. 1870

Collection of Museum of Early Trades & Craft

This stoneware crock was made at the Connolly & Palmer pottery in New Brunswick, New Jersey – the pottery stamped its name and hometown on the back. This kind of stoneware gradually replaced red earthenware in the nineteenth century as people began to realize the toxic dangers of lead glaze. New Jersey produced more clay for stoneware than did any other state by the 1870s. Stoneware potters often added birds and floral designs to their vessels, painted with a cobalt blue that stands out against their buff backgrounds.

Plate and Gravy Boat, Mercer Pottery, c. 1870

Collection of Museum of Early Trades & Craft

New Jersey produced more than crocks and jugs for the table. This fancy plate and gravy boat, made from a hardy type of earthenware called graniteware and painted with delicate floral designs, came from the Mercer Pottery in Trenton, New Jersey. It was one of 15 potteries operating in Trenton around 1870. Notice the difference between this fancy tableware and the stoneware crock produced around the same time. Unlike the stoneware potters, the Trenton potters competed directly with English imports.

Terra Cotta Ornament, Perth Amboy Terra Cotta Company, c. 1890

Collection of Friends of Terra Cotta

Unglazed terra cotta ornaments like this one were inspired by Neo-Classical designs. The popularity of these designs during the nineteenth century makes it difficult to match terra cotta fragments to a specific company until the early 1900s, when the industry consolidated to just a few large firms. The Perth Amboy Terra Cotta Company marked this piece – the stamp bearing the company’s name is faintly visible on its top edge.nd the same time. Unlike the stoneware potters, the Trenton potters competed directly with English imports.

Design Book, “Grammar of Ornament”, Matawan Tile Company, c. 1910

Collection of Middlesex County Office of Culture and Heritage, Division of Historic Sites and History Services

Modelers kept books like this around the shop and used their color plates showing Greek, Roman, and Egyptian designs for inspiration. By the late 1800s, terra cotta companies hired highly-trained modelers who earned over twice the salary of their unskilled counterparts in the factory. They brought their art school books with them and translated the illustrations into plaster and clay.

Terra Cotta Modeling Tools, Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Company, c. 1945

Collection of Middlesex County Office of Culture and Heritage, Division of Historic Sites and History Services

This toolkit belonged to Stephen Kermondy, a modeler at the Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Company in Woodbridge, New Jersey. Modelers created plaster molds for larger pieces, which pressers packed with clay to create the finished piece. For small samples and more intricate designs, the modelers worked directly with the clay. The modeler’s tools were simple – wooden and metal implements twisted into different shapes – but a skilled hand made them work wonders.

Terra Cotta Practice Bomb, c.1918

Collection of Richard Veit

New Jersey terra cotta companies did their part during World War I by producing over 500,000 of these twenty-pound practice bombs for the U.S. military. Specialists stuffed the hollow clay tubes with flour or powdered plaster and dropped them onto practice targets, judging their aim by the white debris left behind. With the men away at war, women helped to staff the factories.

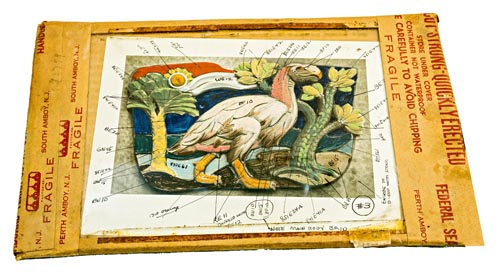

Polychrome Griffin Sampler, Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Company

Collection of Middlesex County Office of Culture and Heritage, Division of Historic Sites and History Services

The many colors on this griffin represent the shades of glaze available on Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta in the mid 1900s. Terra cotta firms first explored colored glazes in the early 1890s with the help of tile companies. Color reached New Jersey terra cotta by 1895, and became especially popular during the Roaring Twenties. Hit hard by the Great Depression and changing architectural styles, terra cotta companies aggressively promoted color in the 1930s and 1940s in an effort to stay alive.

Polychrome Terra Cotta Wasters, c.1930s

American Flag: Collection of Middlesex County Office of Culture and Heritage, Division of Historic Sites and History Services. Green: Collection of Richard Veit

Researchers discovered these two chunks behind closed terra cotta factories in Woodbridge and South Amboy, New Jersey. The companies discarded the pieces, probably because of problems with the glaze or cracking in the kiln. These rejects are called wasters. The tall green piece was recovered from a 400-foot retaining wall of terra cotta wasters behind the former South Amboy Terra Cotta Company.

James Library Terra Cotta Finials, ca. 1899

Two unique features of this building are the twin 116 year-old terra cotta finials that adorn the tower. These architectural details are original to the structure and can be seen in period photographs of the building. As part of a long term restoration project, both fleur-de-lis finials were removed in 2015 for repair and replication, and the original metal rod mountings are now visible above the roofline. One of the finials is intact, but the other had cracked in three places over the years.

As part of this restoration project of the James Library Building, METC retained the services of Historic Building Architects, LLC to map the intact finial with a 3D CAD program. This 3D image will be used by one of the remaining architectural terra cotta companies in the US to replicate the damaged finial.

Modern New Jersey Potters

Potters in New Jersey today work with many varieties of clay and continue to experiment with new techniques. On display were pieces made by two local potters and demonstrate how people are still finding new ways to work with clay.

Mimi Stadler, Hillside, NJ

“My husband and I were walking through a street fair in Greenwich Village and I bought the last four mugs from a potter there. They were blue and gray with specks of brown showing through the glaze. The more I looked at them and used them, the more I thought, ‘I can do this.’ Little did I know it takes lots of practice to make even a simple mug.” – Mimi Stadler

Jane Biron, Chester, NJ

“Most everything I make starts out as a drawing or a photograph. I always use high-fire clay so that I can fire my pieces with whichever technique I think will be most beneficial. I use an electric kiln, a pit-fire, Raku, salt and Anagama – depending on the look I’m after. And each of these techniques has their own methods of firing. I thoroughly enjoy the actions necessary to take the clay from lump to functional vessel or to a sculpture. The whole process satisfies my need to express myself in a tactile medium. – Jane Biron

“Opening a kiln is akin to opening a gift. Even if you don’t get what you want, it’s still a wonderful surprise.” – Jane Biron

Thank You To Those Who Made This Exhibit Possible

- Jane Biron

- Friends of Terra Cotta (Special Thanks to Susan Tunick)

- Middlesex County Office of Culture and Heritage, Division of Historic Sites and History Service (Special Thanks to Mark Nonestied)

- Passaic County Historical Society

- Mimi Stadler

- Dr. Richard Veit

- Special Thanks to Exhibition Interns: Cathy Walter and Emily Cataquet