Cholera to COVID-19

Cholera to COVID-19

Epidemics, Pandemics & Disease

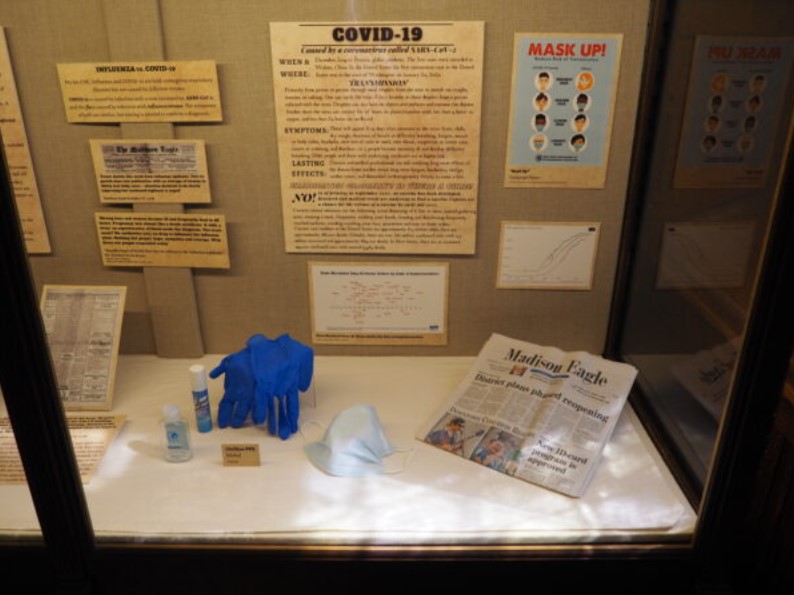

Disease knows no gender, age, class, ethnicity, or country borders. At the end of 2019, a new disease emerged, COVID-19 or the novel coronavirus. COVID-19 has affected the lives of millions in America and billions across the globe. However, this is not the first disease to exert its influence on a national or global scale.

Cholera to COVID-19: Epidemics, Pandemics, & Disease, explores infectious diseases that plagued our nation in the 18th and 19th centuries such as smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis. These diseases provide a unique perspective from which to view the vast improvements in medical practice, healthcare technology, hygiene, sanitation, and overall scientific knowledge of germs, vaccines, and the origin of disease. Walk through this exhibit and examine the resources, tools, and techniques used to diagnose and treat patients during these historic outbreaks. This exhibit intends to reveal the pervasive impact disease had upon daily life, but more importantly how resilient Americans were throughout instances of widespread illness.

Disease Dilemmas

Are you up for the challenge?

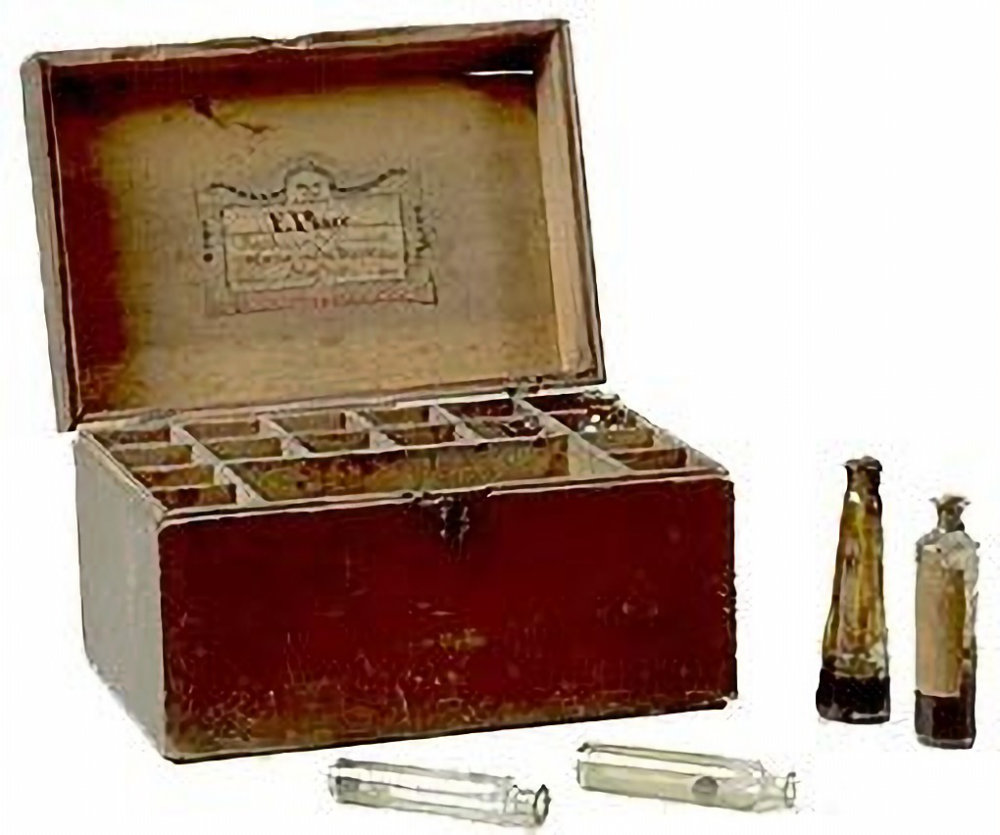

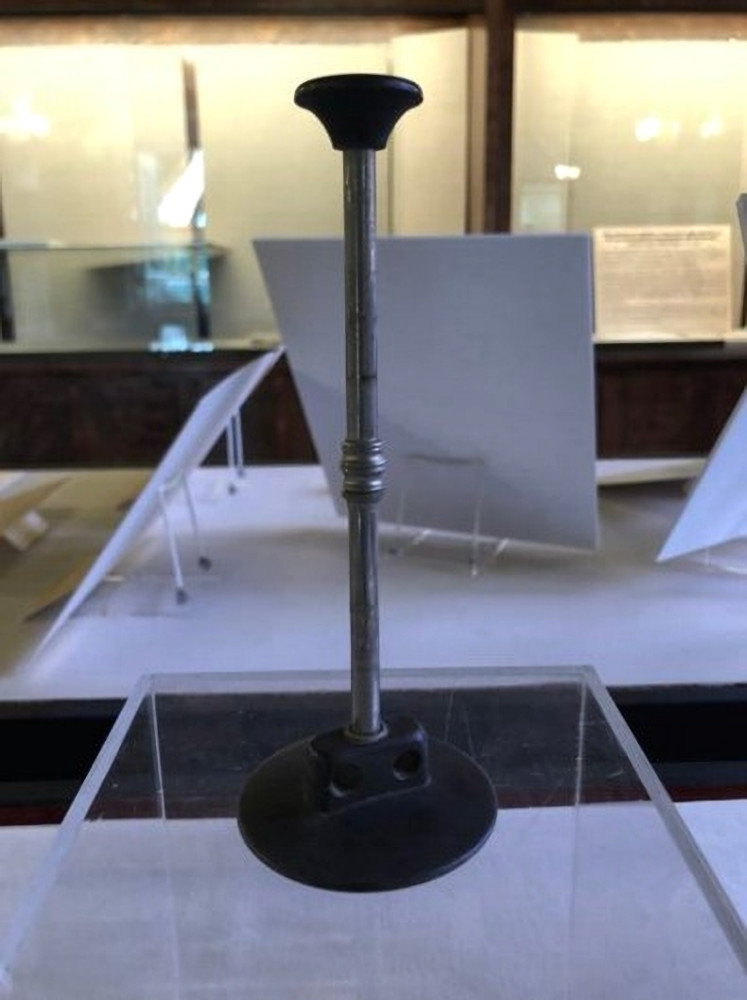

Imagine it! You are a 18th or 19th century medical practitioner. A patient describes their symptoms. Could it be cholera or maybe typhoid? Using the set of symptoms, prescribe your possible cures, treatments, and even medical tools to help your patient recover from the disease! Are you up for the challenge?

There are no upcoming events at this time.

Explore Part of the Exhibit!

Click to expand any area of interest

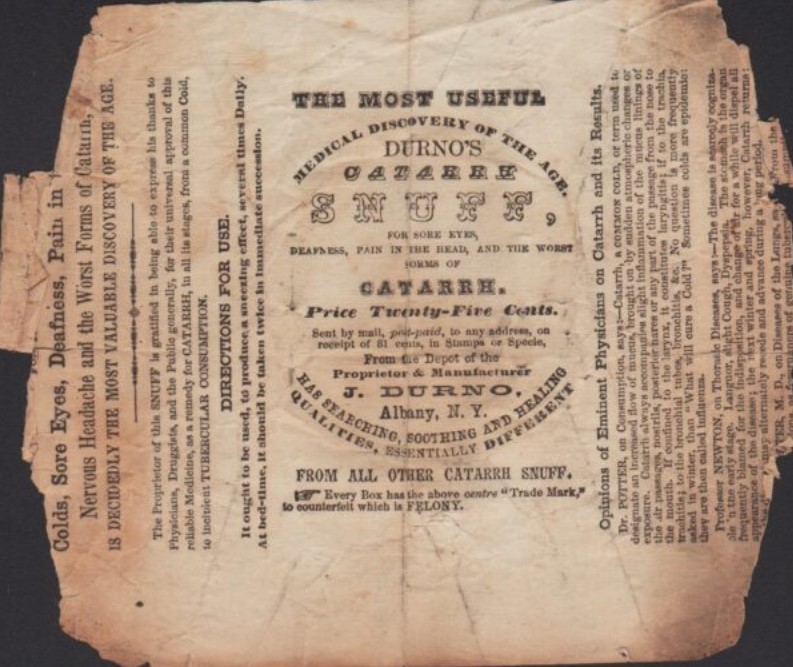

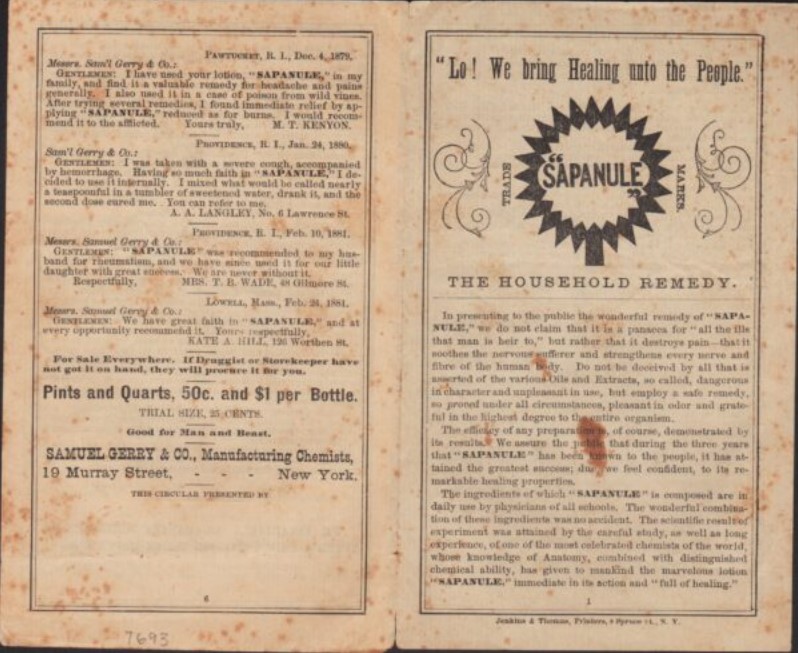

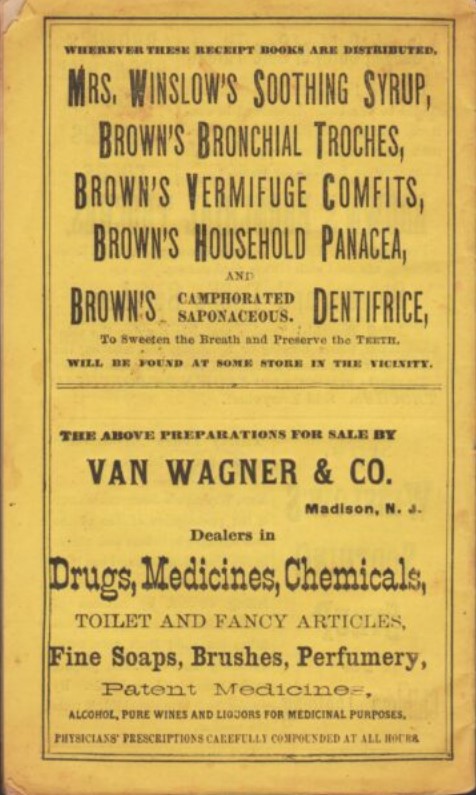

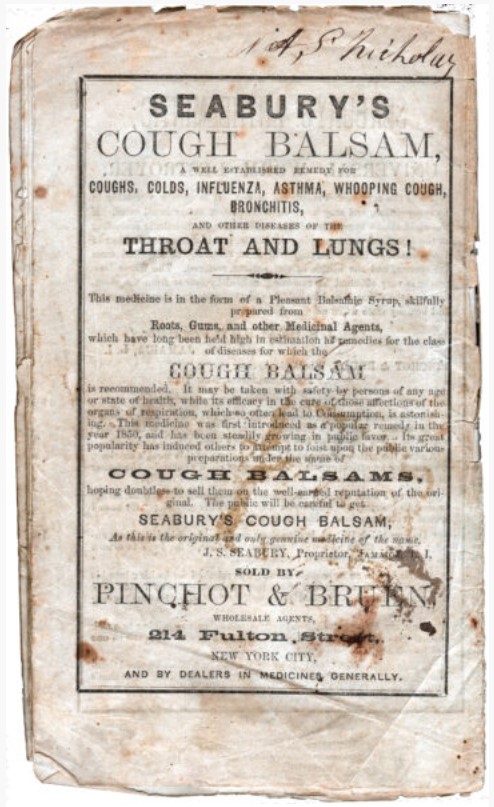

These advertisements for “curious concoctions” and other remedies were sold at apothecaries or drugstores in the 19th century. Many of these advertisements were featured in “receipt books” (or recipe books as we know them today!). All of these are from METC’s collection showcasing a wide array of cures and remedies offered in the 19th century.

Would you dare to try any of these curious concoctions?

Medical training and practice in the 18th & 19th centuries was far from the standardized profession of today. To learn the trade, individuals trained under physicians as apprentices, received formal medical education, or were self-taught and self-certified. Medical schools of the era remained relatively small, unlicensed, and sometimes poorly equipped. There was little regulation to the practice, and it was not required that the individual was formally educated. In 1847, the American Medical Association was founded further standardizing the field of medicine. Professionalization of the trade continued with more reforms in the late 19th century.

Lack of scientific breakthroughs and professionalization in the medical field led many Americans to seek alternative medical treatments, such as homeopathy, spiritualism, hydropathy, Thomsonians or herbalists, and folk remedies. Other medical and pharmaceutical practitioners prospered on the market in the 18th and 19th centuries, such as druggists and apothecaries. Apothecaries sold medicines, practiced patient care (like a physician), and sold other goods.

Epidemics and pandemics of the 18th & 19th centuries characterized the drastic advances yet to come in medicine and the general understanding of disease. Before the groundbreaking developments of antibiotics and immunizations, infectious disease was the greatest threat to life. These diseases struck young, old, and those in the prime of their life.

“Many diseases are infectious. Every person ought, therefore, as far as he can, to avoid all communication with the diseased.” – Domestic Medicine, William Buchan, M.D. (1828)

Transportation, travel, and trade were – and still are – the deadliest modes of mass transmission for disease. European colonization brought smallpox, measles, and influenza to the New World which greatly affected the indigenous people and resulted in devastating mortality rates. Transatlantic slave trade imported malaria and yellow fever to the Western Hemisphere via insects attaching to human hosts. Continued immigration to the continent and wars between nations – specifically the Revolutionary War – created additional avenues for disease spread.

Despite continued transmission of disease, developments were on the horizon for cures. In 1796, English physician Edward Jenner developed a preventative treatment for smallpox. One of the greatest achievements in the medical field during this time, Jenner administered cowpox instead of inoculation with smallpox.

The Complete Herbalist was published in Jersey City, New Jersey, this book outlines alternative remedies, specifically those of the plant variety, for disease and other maladies including smallpox. In Dr. Brown’s introduction he notes: “I do not propose to ‘run a tilt’ against any of the systems of Medical Practice, however much some of them may be opposed to common sense and reason, and to the Divine ordinances of Nature.” Born in the United States in 1825, Dr. Brown was greatly interested in herbal cures. By 1850, he established a medicine business in New Jersey.

Infectious diseases like cholera and typhoid thrived in the 19th and early 20th century due to innovations in transportation and population density in cities. Overcrowded cities with privies and wells for drinking water situated closely together were the perfect storm for intestinal diseases to multiply. Recurrent epidemics raised concerns for sanitation improvements, although many of these were not implemented until the late 19th or even into the 20th century. For example, in the late 19th century, Newark, New Jersey government officials replaced polluted water from the Passaic River with clean water from the Pequannock Watershed to reduce mortality rates from intestinal diseases like typhoid.

Crowded housing in New Jersey’s cities, like Newark and Jersey City, contributed to high rates of tuberculosis due to windowless rooms or lack of ventilation in tenement houses or frame dwellings. Tenements were a breeding ground for disease in all the Garden State’s industrial centers but did not compare to the scale found in New York City.

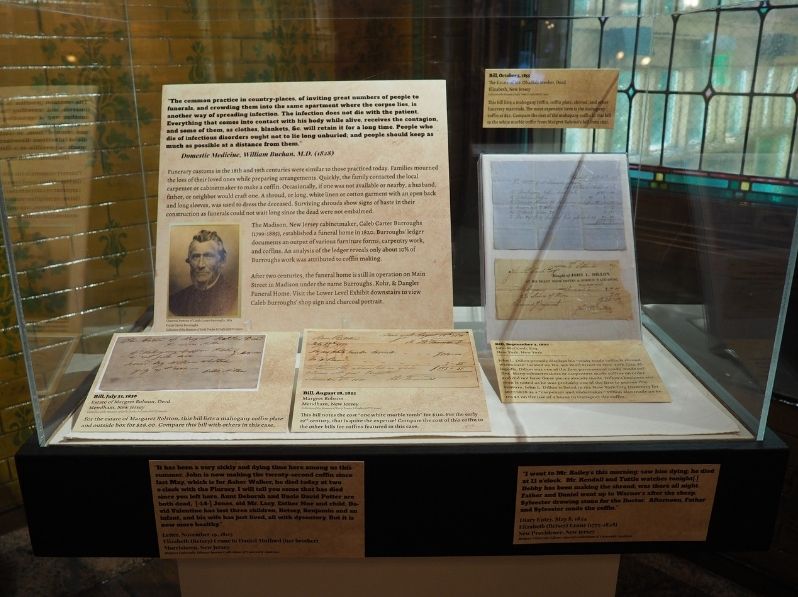

Funerary customs in the 18th and 19th centuries were similar to those practiced today. Families mourned the loss of their loved ones while preparing arrangements. Quickly, the family contacted the local carpenter or cabinetmaker to make a coffin. Occasionally, if one was not available or nearby, a husband, father, or neighbor would craft one. A shroud, or long, white linen or cotton garment with an open back and long sleeves, was used to dress the deceased. Surviving shrouds show signs of haste in their construction as funerals could not wait long since the dead were not embalmed.

The Madison, New Jersey cabinetmaker, Caleb Carter Burroughs (1799-1885), established a funeral home in 1820. Burroughs’ ledger documents an output of various furniture forms, carpentry work, and coffins. An analysis of the ledger reveals only about 10% of Burroughs work was attributed to coffin making.

After two centuries, the funeral home is still in operation on Main Street in Madison under the name Burroughs, Kohr, & Dangler Funeral Home. Visit the Lower Level Exhibit downstairs to view Caleb Burroughs’ shop sign and charcoal portrait.

Testimonies from METC’s Share Your Story initiative reveal the trials and tribulations faced by New Jersey natives and Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read these stories and walk around the exhibit to view other recollections from 18th & 19th century epidemics and pandemics. Participate in METC’s Share Your Story Project with your Share Your Story Snippet by clicking here!

Testimonies from METC’s Share Your Story initiative reveal the trials and tribulations faced by New Jersey natives and Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read these stories and walk around the exhibit to view other recollections from 18th & 19th century epidemics and pandemics. Participate in METC’s Share Your Story Project with your Share Your Story Snippet by clicking here!

Explore nuestra exhibición en español. ¡Haga clic aquí para la traducción al español!